The Gospel of Creation

The Saint Anne Creation Care Committee continues its deep dive into the second chapter of “Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home.” Pope Francis turns from an exposition of various illnesses afflicting the world and the human family to the development of a “treatment plan” rooted in faith and the Bible. Today we look at four more elements of the Gospel of Creation.

4. The Message of Each Creature in the Harmony of Creation (#84-88)

Each part of creation has a God-given purpose, reveals God’s goodness and generosity; it is interdependent and, in some way, reveals God without being able to capture the fullness of God (#84- 88). This approach is beautifully expressed in St. Francis’ Canticle of the Creatures (#87), the inspiration for the encyclical.

The Canticle of St. Francis of Assisi

Praised be to you, my Lord, with all your creatures, especially Sir Brother Sun, who is the day and through whom you give us light. And he is beautiful and radiant with great splendor; and bears the likeness of you, Most High. Praised be to you, my Lord, through Sister Moon and the stars, in heaven you formed them clear and precious and beautiful. Praised be to you, my Lord, through Brother Wind, and through the air, cloudy and serene, and every kind of weather through whom you give sustenance to your creatures. Praised be to you, my Lord, through Sister Water, who is very useful and humble and precious and chaste. Praised be to you my Lord, through Brother Fire, through whom you light the night, and he is beautiful and playful and robust and strong.

Canticle of the Creatures in Francis of Assisi: Early Documents, New York-London-Manilla, 1999, 113-114.

5. A Universal Communion (#89-92)

Love for creation, however, cannot obscure the “pre-eminence” of the human person, and at times “more zeal is shown in protecting other species than in defending the dignity which all human beings share in equal measure” (#90). “A sense of deep communion with the rest of nature cannot be real if our hearts lack tenderness, compassion and concern for our fellow human beings” (#91). Care for the natural world is fine as long as we do not ignore our brothers and sisters who are suffering. These two concerns are related: “when our hearts are authentically open to universal communion, this sense of fraternity excludes nothing and no one. It follows that our indifference or cruelty towards fellow creatures of this world sooner or later affects the treatment we mete out to other human beings” (#92).

6. The Common Destination of Goods (#93-95)

Because the earth and its goods are essentially “a shared inheritance,” Pope Francis reminds us that, in the words of St. John Paul II, “there is always a social mortgage on all private property” (#93).

Our natural environment is “a collective good” and everyone’s responsibility (#95).

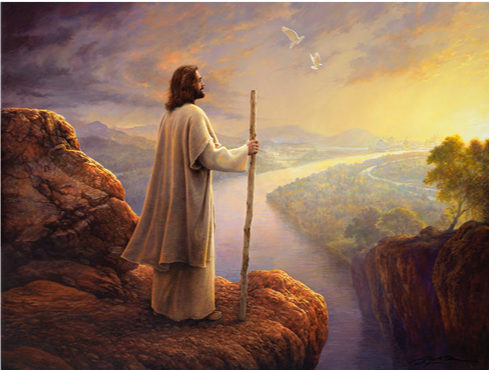

7. The Gaze of Jesus (#96-100)

As Christians we exercise that responsibility following the example of Jesus, who invited people to contemplate the goodness and beauty of the world, lived in harmony with nature, and worked with his hands, thus sanctifying human work (#96-98). Recognizing the honor and responsibility of our calling to live and work as Jesus did, we can face with courage the human roots of the crisis that currently confronts us.

Chapter II concludes with the heart of Christian revelation: “The earthly Jesus” with “his tangible and loving relationship with the world” is “risen and glorious, and is present throughout creation by his universal Lordship” (100).

Summary quote of this chapter’s message:

“We are not God. The earth was here before us, and it has been given to us…. Although it is true that we Christians have at times incorrectly interpreted the Scriptures, nowadays we must forcefully reject the notion that our being created in God’s image and given dominion over the earth justifies absolute domination over other creatures.

The biblical texts are to be read in their context, with an appropriate hermeneutic, recognizing that they tell us to ‘till and keep’ the garden of the world (cf. Gen 2:15). ’Tilling’ refers to cultivating, ploughing, or working, while ‘keeping’ means caring, protecting, overseeing, and preserving. This implies a relationship of mutual responsibility between human beings and nature. Each community can take from the bounty of the earth whatever it needs for subsistence, but it also has the duty to protect the earth and to ensure its fruitfulness for coming generations” (#67)

Questions for Reflection

- How might this encyclical cause us to read and interpret St. Francis’ Canticle of the Creatures in new ways?

- Given the “pre-eminence” of humanity in creation, what does it mean for us to obey God’s command to the first humans, created in the divine image, in Genesis 1:28ff?

- How can the vow and tradition of evangelical poverty help others to better understand and treat the environment as a “collective good?”